In her fascinating series, Laira Gold explains how Buddhism can teach us how to be more successful horsemen.

Horses are wonderful teachers of patience. That old saying, ‘Go about something like you have 15 minutes and it will take all day. Go about something like you have all day and it will take 15 minutes,’ is so true. I think this is something we can all identify with. How many times has your horse refused to cooperate when you have really wanted that end result, to the point of becoming a little, well, desperate? When a horse feels this state of mind in his human handler, it is as though he is saying, ‘You can’t have it when you ask like that.’

As a certified Monty Roberts Instructor, I have been intrigued at the many parallels between Monty’s principles and psychotherapy or counselling – my other profession. When talking about the way horses learn, Monty suggests it is our job to create the right conditions for learning, however, once the horse is ready to draw that information in, it is then our job to get out of the way. As a psychotherapist, this phenomenon is exactly the same with human clients. It’s a paradox – the keener the therapist is for the client to reach their goals, often the longer the client’s process takes. This is because by attaching ourselves so rigidly to the outcome, we are actually getting in the way of the client’s process.

BUDDHA

Interestingly, this teaching is also in line with the Buddhist concepts of attachment and self-grasping. Buddhism teaches that since nothing is permanent and we are all connected, it is madness to place so much power on grasping at external things - be it people, physical objects, goals or ideas and beliefs about ourselves. One of the biggest misinterpretations about Buddhism is that by practising non-attachment, it must mean we lack passion, ambition and do not care about the outcome. This is not the case. Buddhism, like good horsemanship, teaches us the art of having a clear intention but then letting go of the end result. Another way of thinking about this phenomenon is through the idea of pressure zones.

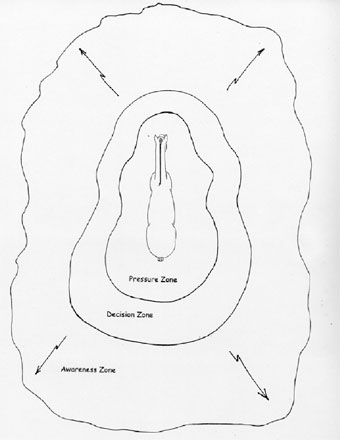

Monty Roberts identified three zones around the horse

The one the furthest away from the horse could be considered the zone of awareness. You know you are in this zone because the horse might look up at you and acknowledge your presence but you are too far away from the horse to be able to drive him forward or draw him towards you. As you move closer, the next zone is the decision-making zone. For some horses out in the wild, this threshold will be miles away, however, for domestic horses, it’s likely to be a lot nearer. In the decision-making zone, you are in a good position to influence the horse’s choice about where he places his feet. If you were to jump up and down and shake some plastic bags, you could probably cause the horse to move away from you for example. It’s in this place that most groundwork takes place. When we get even closer, however, we reach the ‘into pressure’ zone.

Camping out in this zone can cause problems when we are unaware of the phenomenon and the effects it has. Horses are ‘into pressure’ animals. The most common example of this is when a horse stands on your foot and the more you lean, the more the horse leans back into you. They have evolved this way to protect themselves from predators that already have a hold on them. By leaning back into the pressure of the predator, they still stand a chance of dismantling them. If they carried on running, they are likely to cause more damage to themselves. This is how the into pressure trait has evolved.

One recent encounter I had regarding this involved an untouched three-year-old called Alto. I was training Alto to accept touch on his back legs. In this photo above, you can see his whole body curling around the wooden stick I am placing onto his hindquarters. For Alto this stick represents a predator and because it is already close into his body, it makes more sense to move into it than run away.

Sometimes students who are learning to move the horse around in the round pen can step into this pressure zone without realising it. They wonder why the horse isn’t moving away from them. No matter what they do, the horse will not move its feet and will sometimes even lift a back leg to let that person know they are too close. Of course, being human, the biggest temptation when something is not going right is to move in closer, getting more and more attached and rigid. The more desperate we are to achieve our goals, the less effective we seem to be though. By staying back in the zone of influence physically and mentally, not only are we respecting the horse’s personal space and our own, ironically we are probably going to be more effective too.